We had the pleasure of speaking to Ashley Weaver-Paul, House Manager of Emery Walker's House about historical and craftmanship values behind the residence.

On the north bank of the River Thames, between Chiswick Mall and Lower Mall, sits an unassuming street of tall, narrow, Georgian houses. Hammersmith Terrace, has, as the author AP Hubert noted “something of Venice and something of the sea” about it. A hot spot for creatives for more than a century, one house in particular has become a place of pilgrimage. For good reason: step through the front door of No.7, and be transported straight to another time. Once the home of Sir Emery Walker, typographer, printmaker and Arts & Crafts pioneer, this unassuming brown brick and stucco Georgian house contains one of the best-preserved Arts & Crafts interiors in Britain.

Of the countless treasures within the walls of the Emery Walker House it is actually the walls themselves which are one of the biggest draws. Or rather, what’s on them. Thanks to Walker’s close friendship with William Morris, who also lived nearby, the entire four-storey house is adorned with original block-printed wallpapers by the designer throughout, as well as carpets, textiles and embroidery. The overall effect is stunning.

By the start of the 20th century – Emery lived here from 1903 to 1933, when he died – the Arts & Crafts movement was in full swing. Both Emery and Morris had played hugely important roles in the revolution, a backlash against the impersonal direction of a newly industrialised society, promoted a simpler, more fulfilling way of living. The beauty of the handmade, the satisfaction of true craftsmanship, and thoughtful human creativity were duly celebrated. Ashley Weaver-Paul, manager of the Emery Walker House, tells us more about this extraordinary residence.

How did the house come to be preserved as a museum?

AWP: After Emery Walker died, his daughter Dorothy inherited the house. She kept the interior as it was. Dorothy did not marry or have any children, and in the 1950s she advertised for a companion in The Lady. A woman from the Netherlands, Elizabeth De Haas, answered her ad. Elizabeth had never been to England, but she came over and lived with Dorothy until Dorothy died in the 60s.

It was Elizabeth who realised that this house was full of amazing carpets and textiles and wallpapers and the collection was really special. Before she died, she sold Emery Walker's personal collection of books, including those from the Dove's Press, which he founded, and the Kelmscott Press, which was William Morris's printing press.

Through that the museum was endowed in 1999, and it was set up to preserve the house exactly as is. Since then we have also received a Heritage Lottery Fund grant enabling us to restore, catalogue and conserve the collections.

Can you walk us through some of the things a visitor will see?

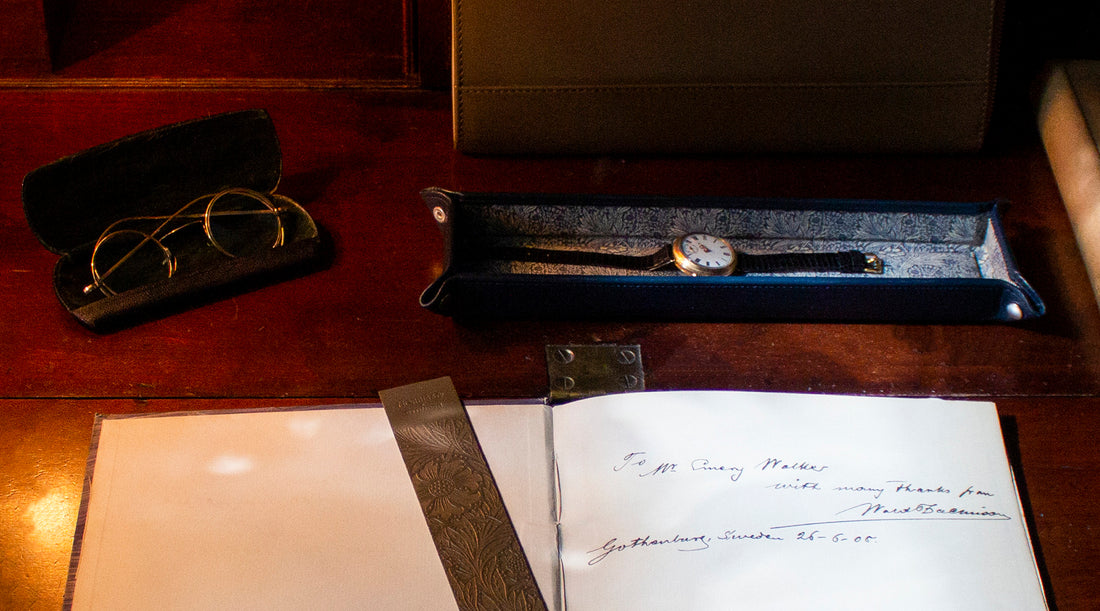

AWP: The museum itself is set up as it was when the Walkers lived here. Everything is in situ. We've got furniture that came from Phillip Webb’s personal cottage, furniture and textiles that belonged to William Morris, beautiful Arts & Crafts ceramics as well as all the knick-knacks and curiosities that make this feel like a family home. There are also many photographs, often taken by Emery himself, of his friends and colleagues, who were leading cultural figures of the day.

There are lots of very personal pieces that were made by friends and the family that were part of the circle of the Walkers. For example, a cushion that was embroidered by May Morris, William Morris' daughter, who was a very skilled embroider, monogrammed May Morris to Emery Walker.

Silk cushion designed by May Morris and embroidered by Dorothy Walker (Image by Emery Walker House)

Tell us about the wallpaper...

AWP: We’ve got one of the largest in situ collections of original Morris hand-blocked wallpapers in England. They are all over the house - every room is covered in wallpaper. The only room that doesn't have wallpaper is the loo. We've got some really special examples of different patterns that are quite rare. There are six designs in total, including Willow and Willow Bough, Daisy, Poppy, Marigold, Wallflower and Apple, all from William Morris’s most prolific creative period during the 1870s and 1880s.

We are seeing a surge in popularity for the Arts & Crafts aesthetic – why do you think that is?

AWP: I agree, I think after years of modernism and minimalism more traditional and maximalist décor and fabrics are really finding their appeal again. However, Morris fabrics and patterns are timeless. They are always in style and have long been the background of traditional decoration. I overhear a lot of people walk into this house and comment, "I could live here." It does feel very cosy and homely.

What is it about them that makes them so timeless, do you think?

AWP: I think both Morris's attention to detail and the way that he uses natural and organic forms to inspire and create his patterns have a lot to do with it. His work captured the beauty that we find in every day. Many of his designs are very much informed by the nature that surrounded him when he was creating them. For example, Willow Bough – in many ways one of his most famous patterns – was inspired by the willows that he saw along the riverbanks out near Kelmscott Manor in the Cotswolds.

In 2022 we launched the Morris & Co X Ettinger Collection to celebrate British craftsmanship and design

What are some surprising things that most people not know about William Morris?

AWP: He was very keen to be part of the private press movement. He had tried to get involved in the movement before Kelmscott Press. He spent quite a lot of time in Iceland! He was very inspired by his travels in Iceland, which you can read about in his journals.

Did you know his daughter, May Morris was also a textile designer? She designed some of his wallpapers as well. She was also very much inspired by nature. It was something that was really important to the Morris family.

As an insider, what are your personal highlights of the Emery Walker House?

AWP: The number one highlight for me would be the coverlet that is found in the bedroom. It was embroidered by May Morris, It's a very intricately embroidered coverlet that was made for Emery Walker's wife. When she died the coverlet was used on her coffin, and then later on Emery's and then on Dorothy's, and finally, on Elizabeth de Haas's.

It's very personal to the family and was clearly made with a lot of love. It's a stunning piece that's incredibly intricate, French knots and wildflowers embroidered all over it.

Coverlet in the bedroom embroidered by May Morris (Image by Emery Walker House)

Discover the Morris & Co. X Ettinger Collection